As with every other scientific field, astronomy is no stranger to the problem of misconceptions held by the public. In many ways, the complexity of the sciences invites such misconceptions to arise, since the theory behind them is often very difficult to understand. In this article, we will explore a few of the most common misconceptions about astronomy.

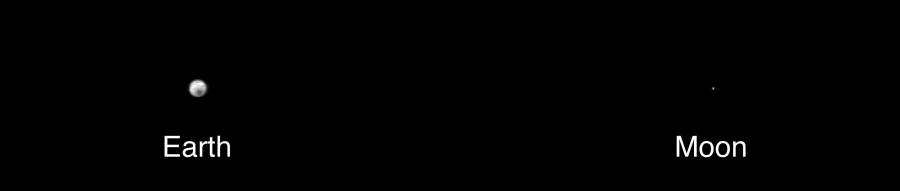

Distances in space. Imagine you have two balls, a basketball, representing the Sun, and a ping pong ball, representing the Earth. How far in relation to each other would the balls have to be positioned, for this scaled-down model to accurately represent the actual distance between them?

This kind of explanations are used all the time, to help us better grasp the mind-boggling sizes and distances, with which astronomy operates. So, what are the most common answers? One meter away? Two? Well, we should start by saying that the size difference between the two balls isn’t representative of the size ratios of the Sun and Earth. If the Sun was the size of a basketball, the earth would be just a bit larger than a grain of rice, and it would be orbiting our basketball Sun from a distance of 25 meters away, way farther than people usually imagine (Brian W. Miller & William F. Brewer 2009).

So, why is that? One of the reasons probably lies in the way that our solar system is represented in popular science and even textbooks. Whenever we see a diagram of the planets and the Sun, they all fit on one page, with the Sun taking up three or four times as much space, as the rest of the planets, while in reality, it should be hundreds of times larger than most planets, and the planets should not fit on the same page, in fact, the outermost ones would be tens of meters away, which, for people making textbooks, isn’t really practical. I do believe that this issue could be addressed by using computer simulations, which have the ability to “scale-up”, and show detailed models of the planets, while at the same time retaining the right proportions when it comes to distance and size.

Nothing can move faster than the speed of light. As Einstein famously postulated, nothing can exceed the speed of light in a vacuum. And, since Einstein and part of his work are well known amongst the masses, most people accept this statement as a fact. But the problem arises when you look at objects half a universe away. There is a large part of the universe, which is moving away from us, at a speed greater than the speed of light. But how can that be true, since we all know Einstein was a genius?

Well, Einstein and his genius aren’t being contested with this phenomenon, because in this situation the galaxies which are moving away from us, aren’t actually traveling faster than the speed of light, it’s the space between us, which is expanding. Most people don’t realize that the universe is (and I am simplifying this greatly) like a balloon with galaxies drawn on its surface. With time that balloon is growing, and thus, the distances between the dots are expanding as well. And with distances as great as we are dealing with in this case, the speed at which that distant part of the universe is being “moved” away from us due to all the newly created space, is bigger than the speed of light, without anything actually moving faster than the speed of light, thus keeping Einstein’s genius intact (Tamara M. Davis & Charles H. Lineweaver 2003).

How to tackle this misconception? Well, in this case, the preconception is correct, since the laws of relativity hold, but the fact that there are scenarios in which the result doesn’t necessarily meet the expectations of a person, based on their knowledge, can be problematic. And while these kinds of problems are not likely to cause any difficulties in day to day life, they should be taken into consideration. Teachers and science communicators should pay attention to caveats like this one, and at least mention them to their audience.

There is no gravity in space. When people see footage from the International Space Station, with astronauts floating around their environment, they mostly assume, that it is due to the fact that in space, the gravitational pull of the Earth is negligible. While it is true, that the force of gravity gets smaller with the distance to the object squared, but for the ISS, which is orbiting at roughly 400 km from the surface (compared to the surface being 6400 km away from the center of the Earth, which is where the force of gravity originates from), that gives us a value of about 90% of the force of gravity felt on the planet’s surface. The floating comes from the fact, that the entire ISS is in constant freefall, all the time falling towards the Earth, but due to the speed at which its flying perpendicular to the surface, its path is following the curvature of the planet, thus missing it.

This misconception is the product of two ideas, one is related to the first misconception which I mentioned in this article, people assume that the ISS is much further away when in reality, it’s almost skimming the surface of the planet. And the second problem has to do with their personal experiences, what they are being shown whenever they see astronauts in space. This problem has to be tackled in the classroom, where special emphasis should be given to this very problem, because it isn’t very intuitive, and yet, is quite important and interesting.

Gaber I

Sources:

Brian W. Miller & William F. Brewer 2009, Misconceptions of Astronomical Distances, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Ch online, Page 1549-1560

Tamara M. Davis & Charles H. Lineweaver 2003, Expanding Confusion: Common Misconceptions of Cosmological Horizons and the Superluminal Expansion of the Universe

http://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/5-8/features/nasa-knows/what-is-microgravity-58.html